26-06-2013

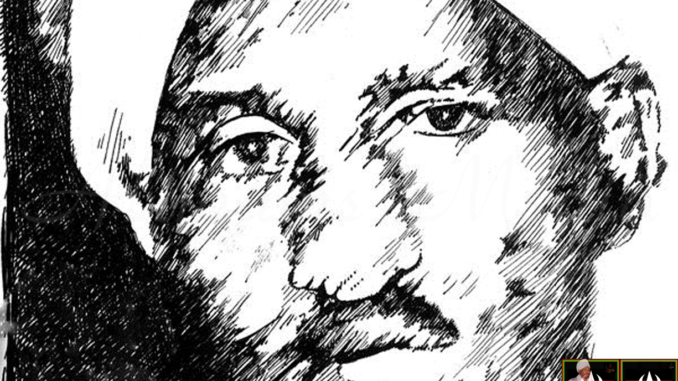

Gamal Nkrumah interviews father and daughter Umma Party political duo, Sadig and Mariam Al-Mahdi

Imam Sayed Al-Sadig Al-Mahdi, as head of Sudan’s National Umma Party and Sudan’s Ansar Movement, had come a long way fast. He became Sudan and Africa’s youngest prime minister at the age of 31. He served as Sudanese prime minister from 1966-67, and again beginning in 1986, a term that ended with the coup of 1989 by the National Islamic Front, a now defunct movement that was headed by Sudan’s chief Islamist ideologue, Sheikh Hassan Al-Turabi, ironically a political rival and head of the opposition Islamist Popular Congress Party (PCP) and Al-Mahdi’s brother-in-law, husband to Al-Mahdi’s sister Wisal. After the coup, Al-Mahdi was imprisoned and tortured. He left Sudan in exile in 1996, but returned triumphantly to the country in 2000 from exile in Eritrea.

Al-Mahdi is an Islamist in orientation, a religious leader of paramount importance in Sudan, even though he clearly advocates a “moderate” as opposed to “militant” strand of Islam. In 2002, Al-Mahdi was elected head of the Ansar Movement, a Sufi Order dedicated to the memory of his great grandfather, Mohamed Ahmed of the Samaniya Sufi Order, the 19th century Sudanese religious leader and the political unifier of modern Sudan.

Sudanese opposition leaders are notorious for turning procrastination into a defining feature of their challenge to Al-Bashir’s political hegemony. Al-Mahdi is easy with people, even with his political opponents. His careful, deliberate style is often attributed to his deep religiosity.

Al-Mahdi presides over a very tight-knit group of close confidants, including his daughter Mariam. His son, Abdel-Rahman Al-Mahdi, in sharp contrast, is a senior presidential advisor to Sudanese President Omar Hassan Al-Bashir. Yet, Al-Mahdi, a seasoned Sudanese politician is ambiguous about this particular relationship between his son and the Sudanese president. “My son Abdel-Rahman is a free-thinking man. He is a nationalist who has Sudan’s national interests at heart. I cannot interfere in his political decisions and I do not like to dictate my political positions or enforce them on my sons or daughters. They are free to choose their political paths,” Al-Mahdi told Al-Ahram Weekly.

Al-Mahdi, like many religious-minded political leaders, has an unmistakable air of serenity about him. It is an attitude that invariably infuriates his political rivals and opponents. His detractors claim that they cannot understand how he always appears to get away with what they describe as his opportunism.

In spite of his relaxed, almost devil-may-care manner, and suave mannerisms, Al-Mahdi cannot mask domestic policy strains that currently grip Sudan. He is optimistic by nature. He says he is not particularly interested in holding high office. He is essentially devoted to democracy, which he believes is the key to unlocking Sudan’s legion challenges.

Opposition to the ruling National Congress Party (NCP) headed by Al-Bashir is growing with a wide spectrum of political parties in Sudan. The economic conditions in the country have deteriorated considerably with the loss of vital oil revenue in the aftermath of the independence of South Sudan in 2011. The intensification of the fighting in the peripheral regions of the country such as Darfur, southern Kordofan and Blue Nile where the disgruntled mainly non-Arab indigenous population are furious about their political marginalisation. Even so, it is often argued that the opponents of Al-Bashir have failed to make political capital in spite of popular discontent over soaring food prices.

I queried Al-Mahdi about the reason behind the Arab Spring uprisings that appear to have largely passed Sudan by. He disagreed, explaining that there have been a number of street protests by university students and workers, but he stressed that the security forces clamped down hard on the protesters. The frequent small street protests by students did not spread, he admitted, partly because they did not coordinate with the political parties. “Unfortunately, the protests were spontaneous and not properly coordinated. Moreover, the political parties failed to organise the protests to achieve specific political goals,” Al-Mahdi expounded.

Al-Bashir, who came to power in 1989, still enjoys the support of the military especially since he purged the army of anti-government forces. Al-Bashir also has the tacit support of several key Arabised tribal confederations in Darfur, Kordofan and other western Sudanese regions in particular, and influential Islamist groups based in urban centres. He crushed challengers to his rule in a 2010 election and dismisses the opposition parties as insignificant.

The National Consensus Forces (NCF), an umbrella of the main opposition parties in Sudan, is calling for a peaceful process of regime change and genuine democratisation. They reject the armed struggle as a political option and instead — as their very name implies — aim at national consensus.

A Sudanese leader in her own right and a distinguished opposition member of the Umma National Party, Dr Mariam Al-Sadig Al-Mahdi is also an advocate for human rights, democracy and women’s rights. Her father is keen to support his daughter and the women of Sudan to have a more influential role in the decision-making process in the country.

“Women must assume more senior and responsible political positions in the country. I fully support the political participation of Sudanese women. I also want to see the youth taking a more active interest in Sudanese politics. And, by youth I mean both young women and young men,” Al-Mahdi noted.

He relaxed in his reclining chair.

“We have lost certain political rights in the past two decades. Sudanese women have traditionally been very active in politics. This is a very serious setback for us as Sudanese women,” Mariam Al-Mahdi chipped in.

“Sudan needs a comprehensive and holistic approach to resolve the country’s political and economic problems. The militarisation of politics in Sudan led to the marginalisation of women,” Mariam Al-Mahdi insists.

“Sudan needs radical reforms at the moment and the NCP needs to radically reform its political, judicial and institutional structures and strengthen the democratic institutions in the country. We in the Umma Party are trying to tackle these problems and to focus the attention on these vital issues. We need to work hand-in-hand with other political parties as well as civil society organisations such as women’s groups,” Mariam Al-Mahdi expounded.

“We are advocating for all the opposition parties to stage a comprehensive conference for peace and political change in Sudan,” she added. The PCP also is dedicated to an agenda of radical political reform. Al-Turabi, like Al-Mahdi, was imprisoned in the Kobar (Cooper) Prison in March 2004. However, both Mariam Al-Mahdi and her father are reluctant to get drawn into the precise relationship between the Umma Party and Al-Turabi’s PCP.

“We are bound to work together as opposition parties,” Al-Mahdi conceded.

The great divide among Sudanese opposition parties in Sudan at the moment is between those who prefer a non-violent, peaceful transition to democracy and those who choose to take up arms against Al-Bashir’s government.

However, Mariam Al-Mahdi, like her father, advocates civil transformation in Sudan and rejects the personal conduct of certain leading members of the ruling NCP — parties whom she declined to name. “There is rampant corruption in the country. We are for civil disobedience, [but] do not pursue change by the violent overthrow of the NCP,” Mariam Al-Mahdi told the Weekly.

Numerous political parties that the Al-Mahdis work with are also interested in peaceful methods of political change. “The regime is very weak at the moment. We will begin today and in the next days to prepare popular demonstrations,” said Farouk Abu Eissa, head of the NCF and a veteran Sudanese politician and former foreign minister.

Abu Eissa said the Sudanese opposition, including the NCF, was collaborating closely with the armed Sudanese opposition alliance, the Sudanese Revolutionary Front (SRF) led by the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N). However, like Al-Madhi and his daughter, Abu Eissa opposes what he describes as the “violent tactics” of the SPLM-N and the SRF.

“The SRF is our strategic partner. We don’t agree with them on using military means, but we share the same goal of bringing down the regime,” Abu Eissa extrapolated.

I asked Al-Mahdi about the economic and political implications for Sudan as far as the construction of the Renaissance Dam on the Blue Nile in neighbouring Ethiopia. Sudan, itself, is going ahead with plans to construct its own mega dam on the Nile, the Meroe Dam.

“Ethiopia is a major mediator — perhaps the main one — between Juba and Khartoum. It is prerequisite to cooperate economically and politically with one of the most important regional powers. Ethiopia has also one of the fastest growing economies in Africa and the world. Therefore, it is vitally important to reach a peaceful agreement between the countries of the Nile Basin, and especially Ethiopia. We need peace in Sudan and the entire region to accelerate economic growth and facilitate development,” Al-Mahdi concluded.

Al – Ahram Weekly